Quentin Tarantino’s movie “The Hateful 8” and the process of nation-building in the USA

Quentin Tarantino’s movie “The Hateful 8” and the process of nation-building in the USA

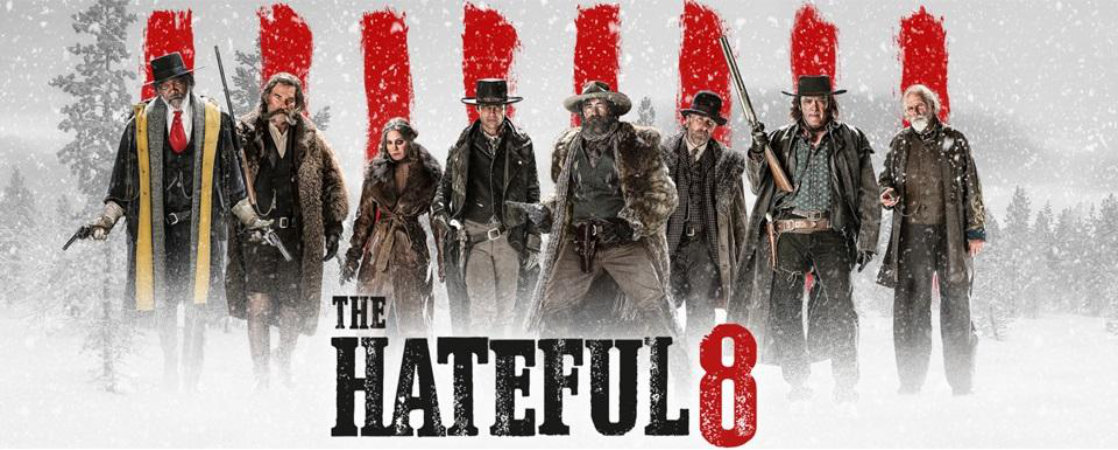

Quentin Tarantino’s film “The Hateful 8” is generally known as a Western, one whose uniqueness lies in the fact that the action is set in a wintery landscape and in a snowed-in log cabin. Otherwise, it is said, the film contains the excessive violence and gory scenes that are typical for Tarantino.

The title itself – “The Hateful 8” – already suggests that the eight main characters in the film have something in common. Since Tarantino generally works with allusions to movie classics and thereby demonstrates a special appreciation of music and sound as a basic component, it would be worthwhile to take a closer look at „The Hateful 8“ in a comparative perspective as well. As a result, it very soon becomes apparent that Tarantino distinguishes his eight main characters through differing parlances and distinct manners of speaking.

But how does this work?

John Ruth, “The Hangman,” a bounty hunter, is heading through the winter landscape toward Red Rock, Wyoming, after the end of the Civil War. With him he has three corpses and a living prisoner, Daisy Domergue, “The Prisoner.” In the middle of the snow, they encounter Major Marquis Warren, “The Bounty Hunter,” who asks them to take him along in the stagecoach. Later they are joined by laid-back Chris Mannix, who claims to be the new sheriff of Red Rock.

Threatened by an impending blizzard, they all stop at Minnie’s Haberdashery, a stagecoach lodge. There they come upon General Sanford Smithers, “The Confederate,” as well as a group of shady men, including Joe Gage, “The Cow Puncher,” Oswaldo Mobray, also known as Pete Hicox, “The Little Man,” and Bob, “The Mexican.”

A double murder is committed, and John Ruth dies from a cup of poisoned coffee. What then follows is the attempt to identify the murderer, using quasi juridical methodology. The closer they come to solving the case, the more the situation escalates, ending in a final bloodbath that is survived only by Major Marquis Warren and Chris Mannix, who has been seriously injured. They, too, will presumably bleed out as well. But before this occurs, they will have defended law and justice and thus the values and foundations of the new USA of Abraham Lincoln.

This is the plot in a nutshell. Who are the eight main characters?

Major Marquis Warren is an African-American soldier who is simply referred to as “The Nigger” most of the time, but sometimes also as “boy” or “son.” As one of the “United States Colored Troops,” he fought against the slavery states in the South. His speech is melodic, his language metaphorical, and his argumentation unerringly factual. His cadence is reminiscent of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” pathos, even when he says: “The only time black folks are safe is when white folks is disarmed.”

Major Marquis Warren is an African-American soldier who is simply referred to as “The Nigger” most of the time, but sometimes also as “boy” or “son.” As one of the “United States Colored Troops,” he fought against the slavery states in the South. His speech is melodic, his language metaphorical, and his argumentation unerringly factual. His cadence is reminiscent of Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” pathos, even when he says: “The only time black folks are safe is when white folks is disarmed.”

He stands for the black population of the USA, so it is not surprising that he shoots General Sanford Smithers fairly soon, as the latter is an embittered representatives of the slavery states.  Ironically, however, Major Marquis Warren turns out to be the one to solve the murder conspiracy at Minnie’s Haberdashery.

Ironically, however, Major Marquis Warren turns out to be the one to solve the murder conspiracy at Minnie’s Haberdashery.

General Sanford Smithers, “The Confederate,” stands for the supporters of the southern states, is unforgiving and bitter and cannot get over his defeat. He does not have much of a future.

John Ruth, “The Hangman,” does not live long enough in this film to be designated to a specific group. But he unmistakably stands for the US legal system, which grants any accused person a fair trial at court and opposes lynch law. He could easily kill his prisoner, Daisy Domergue, but wants to bring her to Red Rock alive, so that she can be hanged there after due process. John Ruth stands for the legal system of the USA, which is to prevail over the frontier law of vigilante justice and over the lawlessness of the outlaws.

John Ruth, “The Hangman,” does not live long enough in this film to be designated to a specific group. But he unmistakably stands for the US legal system, which grants any accused person a fair trial at court and opposes lynch law. He could easily kill his prisoner, Daisy Domergue, but wants to bring her to Red Rock alive, so that she can be hanged there after due process. John Ruth stands for the legal system of the USA, which is to prevail over the frontier law of vigilante justice and over the lawlessness of the outlaws.

His prisoner, Daisy Domergue, speaks an exceedingly bawdy American English, interspersed with the slang of the street, with cursing and swearing.  Her roots must be attributable to French immigrants, and she stands for the traditionally tense relationship between the US and France, for the rivalry between the world’s law enforcers and a group of people made up of smokers and heavy drinkers, who are morally reprehensible and – as they are unreliable – cannot be trusted. Domergue is characterized by other anti-French stereotypes: She is short-tempered, devious – and unkempt.

Her roots must be attributable to French immigrants, and she stands for the traditionally tense relationship between the US and France, for the rivalry between the world’s law enforcers and a group of people made up of smokers and heavy drinkers, who are morally reprehensible and – as they are unreliable – cannot be trusted. Domergue is characterized by other anti-French stereotypes: She is short-tempered, devious – and unkempt.

Chris Mannix, on the other hand, shows the charming and endearingly optimistic California character – friendly, open, direct, and yet somewhat naïve and gullible.  His southern accent is broad and nasal, and he swallows the ends of words, as well as some vowels. He never stops talking, seems superficial, but finally turns out to be reliable and loyal, an honest character who keeps his word. Although he is a so-called Lost Causer, full of admiration for the joie de vivre and the easygoing lifestyle of the South, he is to hang Daisy Domergue near the end of the film, together with Major Marquis Warren – as it were, with his former nemesis – in the spirit of John Ruth. This shared judgement and joint execution of justice by the two former wartime enemies is the remarkable finale of the film, in which the North and the South literally “pull together.”

His southern accent is broad and nasal, and he swallows the ends of words, as well as some vowels. He never stops talking, seems superficial, but finally turns out to be reliable and loyal, an honest character who keeps his word. Although he is a so-called Lost Causer, full of admiration for the joie de vivre and the easygoing lifestyle of the South, he is to hang Daisy Domergue near the end of the film, together with Major Marquis Warren – as it were, with his former nemesis – in the spirit of John Ruth. This shared judgement and joint execution of justice by the two former wartime enemies is the remarkable finale of the film, in which the North and the South literally “pull together.”

The adversary of both of them is, ironically, Oswaldo Mobray aka Pete Hicox, who is immediately noticeable due to his clear, clean British English and stands out from all the others. This is accentuated by his English clothing and the bowler hat he wears. He is well-groomed and polite and has good manners. He is intelligent and tactical, thinks strategically – and is ruthless. The fact that Major Marquis Warren and Chris Mannix have to hold their ground against this very character, Pete Hicox – and also succeed in doing so – represents the unexpected assertiveness shown by the US toward Great Britain, a major power, and the way in which the US has consolidated to confront a perfect state machinery.

The adversary of both of them is, ironically, Oswaldo Mobray aka Pete Hicox, who is immediately noticeable due to his clear, clean British English and stands out from all the others. This is accentuated by his English clothing and the bowler hat he wears. He is well-groomed and polite and has good manners. He is intelligent and tactical, thinks strategically – and is ruthless. The fact that Major Marquis Warren and Chris Mannix have to hold their ground against this very character, Pete Hicox – and also succeed in doing so – represents the unexpected assertiveness shown by the US toward Great Britain, a major power, and the way in which the US has consolidated to confront a perfect state machinery.

Last but not least, there are Bob, “The Mexican,” and Joe Gage, the “Cow Puncher.” Just as Daisy Domergue stands for the French immigrants and Pete Hicox for British interests, Bob represents the Spanish-speaking population in the United States. His American English sounds appropriately “broken” and is interspersed with Latino expressions. The fact that he turns out to be a member of a group of bandits and is sneaky and shifty reflects the derogatory cliché of immigrants from Central and Latin America.

Last but not least, there are Bob, “The Mexican,” and Joe Gage, the “Cow Puncher.” Just as Daisy Domergue stands for the French immigrants and Pete Hicox for British interests, Bob represents the Spanish-speaking population in the United States. His American English sounds appropriately “broken” and is interspersed with Latino expressions. The fact that he turns out to be a member of a group of bandits and is sneaky and shifty reflects the derogatory cliché of immigrants from Central and Latin America.

Joe Gage, finally, represents the so-called average American from the countryside. He is simple-minded and clumsy, but not unpleasant. His speech is slow, and he is rather taciturn. Joe Gage fits the stereotype of a farmer in the dairy or corn belt of the USA. He pretends that he wants to get home to his mother for Christmas, and he plays “Silent night, holy night” on the piano at Minnie’s Haberdashery – the incarnation of the American dream. So it was fitting that the film “The Hateful 8” was released in the USA on December 25, 2015, Christmas Day.

Joe Gage, finally, represents the so-called average American from the countryside. He is simple-minded and clumsy, but not unpleasant. His speech is slow, and he is rather taciturn. Joe Gage fits the stereotype of a farmer in the dairy or corn belt of the USA. He pretends that he wants to get home to his mother for Christmas, and he plays “Silent night, holy night” on the piano at Minnie’s Haberdashery – the incarnation of the American dream. So it was fitting that the film “The Hateful 8” was released in the USA on December 25, 2015, Christmas Day.

Each of these eight characters thus stands for a specific segment of the population of the USA. Together, they make up the new nation after the Civil War. The fact that a shared dispensation of justice still grows out of their hatred is the noteworthy feature expressed by the film “The Hateful 8,” whose theme is thus the process of nation-building in the USA. That one specific group is not seen in this film – that of the Indians – only serves to support this thesis. True, a minor character of Asian origin does appear, but he is immediately shot and dies in the outhouse. This, too, is a (provocative) statement on the US society.

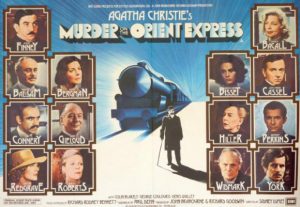

As to references to cinematic history made by Quentin Tarantino in “The Hateful 8,” there are unmistakable parallels with Sidney Lumet’s film “Murder on the Orient Express,” which is based on Agatha Christie’s crime thriller. Sidney Lumet’s “Murder on the Orient Express” is set in the multi-ethnic nations of the Balkans, and the characters in his film speak a large variety of languages and dialects. For example, bits of German are interspersed in the English original. Lumet works with sound just as Tarantino makes use of music in “The Hateful 8.” The beginning of the film, in which the passengers board the Orient Express and in which information is provided regarding an unsolved crime – the murder of a child named Daisy! – has no sound whatsoever. The viewer might question the sound quality of the DVD or whether the volume knob of the DVD recorder is working properly, but Lumet’s film in fact begins with no sound at all, for what seems to be a long period of time.

As to references to cinematic history made by Quentin Tarantino in “The Hateful 8,” there are unmistakable parallels with Sidney Lumet’s film “Murder on the Orient Express,” which is based on Agatha Christie’s crime thriller. Sidney Lumet’s “Murder on the Orient Express” is set in the multi-ethnic nations of the Balkans, and the characters in his film speak a large variety of languages and dialects. For example, bits of German are interspersed in the English original. Lumet works with sound just as Tarantino makes use of music in “The Hateful 8.” The beginning of the film, in which the passengers board the Orient Express and in which information is provided regarding an unsolved crime – the murder of a child named Daisy! – has no sound whatsoever. The viewer might question the sound quality of the DVD or whether the volume knob of the DVD recorder is working properly, but Lumet’s film in fact begins with no sound at all, for what seems to be a long period of time.

The further parallels are even more surprising, however. Like Tarantino’s stagecoach, Lumet’s train is traveling through a snow-covered landscape. However, whereas Tarantino’s travelers have to stop on the open road because of a blizzard, Lumet’s train comes to a halt midway on the snow- and ice-covered tracks due to a rockslide. In Lumet’s film, this gives detective Hercule Poirot an opportunity and the time to solve a murder in the train. In Tarantino, on the other hand, waiting for the blizzard to pass provides the time required to unmask the gang of killers. In both films, therefore, the landscape is not paramount, but is only the set for a kind of chamber play, which takes place in a railroad car for Lumet and for Tarantino first in a stagecoach and then in the closed space of Minnie’s Haberdashery. The landscape is merely the setting, but not the scene of the drama, and Tarantino’s “The Hateful 8” is less a Western than it is a thriller. Tarantino’s Hercule Poirot, the character who solves the murder case, happens to be Major Marquis Warren – a Marquis, at least – in “The Hateful 8,” an African-American who restores governmental order. This is a remarkable political positioning.

In terms of content, “The Hateful 8″ describes the process of nation-building. In form, it is more like a chamber drama than a stage play. The film belongs less or as much to the Western genre than to that of crime thrillers.

The derivation of the events, as carried out by Major Marquis Warren, and the logic with which he reaches his conclusions could easily be seen as an appeal for greater reason in the day-to-day politics of the USA. The key scene in this truth seeking, in which Major Marquis Warren uses the process of elimination to determine who could not be the perpetrator, and thus who must be the perpetrator, is tellingly accompanied by the melody “Silent night, holy night.” So Major Marquis Warren can be seen as a kind of justice of the peace, who relentlessly pursues the logic of the burden of proof and even risks his life to do so.

Quentin Tarantino’s “The Hateful 8” is thus a legal thriller that illustrates how a pack of people thrown together can come to a lawful agreement and then apply it. In Sydney Lumet’s “Murder on the Orient Express,” Hercule Poirot applies his own rules of law. In connection with Tarantino’s film, this means that questions regarding law and justice, complying with and upholding the law, is a societal duty to be performed individually at any time.

© Pictures from “The Hateful 8” are taken from the official film trailer by The Weinstein Company

© of the film poster “Murder on the Orient Express” by Sidney Lumet productions

Schreiben Sie einen Kommentar